The erosion of realism

Even before the turn of the century, in the midst of triumphant bourgeois culture, the certainties of realism began to crumble. The Decadents and Symbolists of the 1880s, of whom the great poster artists were the public face, rejected bourgeois values of Progress and Reason. They used the dark colours lacking in the sunny landscape of Reason. J.-K. Huysmans (1848-1907) considered himself a disciple of Zola; but in 1884 he published his infamous novel A Rebours (Against Nature, or Arse Backwards). Huysmans' hero, Duke Jean des Esseintes, was the last of an 'ancient lineage' in which 'the males were becoming more and more effeminate': 'a frail young man of thirty who was anaemic and highly strung, with sunken cheeks, cold eyes of steely blue, a nose turned up yet straight, and slender, dry hands'.5

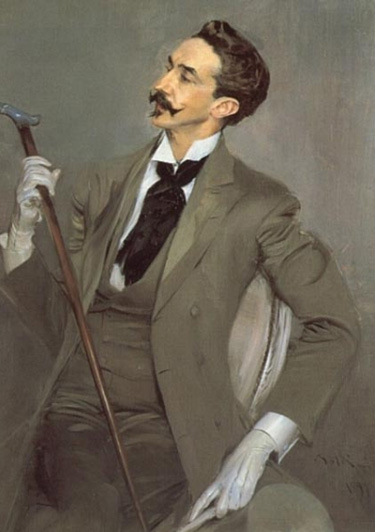

This was, as Robert Nye points out, 'the perfect type of exhausted and degenerate aristocrat' whose loss of manhood and virility seemed to conservative thinkers to epitomise the problem facing France. The Jew, the homosexual and to some extent the intellectual were this terrifying Other. The homosexual or 'invert' was 'an unmanned degenerate'.6 Des Esseintes was modelled on Count Robert de Montesquiou, whose portrait appropri ately graces the cover of the Penguin edition and who was also the model for Proust's Baron de Charius,, another 'invert'.

The duke determined to reverse the rational. In one chapter, he replaced all the plants in his home with artificial flowers, but then, 'sick of artificial flowers mimicking real ones, he wanted real flowers that looked artificial'. He thus bred hideous, degenerate flowers:

Most of them, as if ravaged by syphilis and leprosy, displayed pallid flesh blotched with measle-like spots ...; others had the vibrant pink of a scar beginning to heal or the brown of a scab beginning to

form; ... he had achieved his aim; not one looked real; it was as if

man had lent cloth, paper, porcelain and metal to Nature to enable her to create these monstrosities.7

Giovanni Boldini, Portrait of Robert de Montesquiou (1897)

Gustave Moreau, Salome dancing before Herod (1876)

Moreau was one of the favorite artists of the fictional des Esseintes

Gustave Moreau, Phaeton (1877)

At the end the duke delighted in having to feed himself by enima pumps, thus giving the title a literal sense. Behind the desire to shock lay a new aesthetic, praising artifice instead of Nature, contrariness instead of Reason, and degeneracy instead of Progress.

What terrified conservative commentators delighted a new generation of writers, who saw in the duke's perverted tastes a way out of the dead end of realism. The new decadent aesthetic was soon the 'in' thing. In Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), A Rebours is 'the yellow book' which begins Dorian's initiation into evil. It showed him 'the sins of the world ... in exquisite raiment, and to the delicate sound of flutes': 'One hardly knew at times whether one was reading the spiritual ecstasies of some medieval saint or the morbid confessions of a modern sinner. It was a poisonous book.'

Wilde had not yet read Huysmans' most deeply troubling work, La-bas (Down There- 1891), which involved Satanism and the ritual sacrifice of babies. Perhaps because he was seeking something beyond the material world, Huysmans then moved to devout Catholicism with La Cathedrale (The Cathedral - 1898), which was underpinned by a Symbolist reading of Chartres Cathedral.

The fictional des Esseintes's favourite poet was the real Stephane Mallarme (1842-98), whose 1876 masterpiece L'Apres-midi d'un faune (A Satyr's Afternoon) was a dream of desire which replaced the material world with a psychic one. In 1885, Mallarme returned the compliment in Prose (pour des Esseintes) (Prose for des Esseintes), suggesting that the aim of the artist should be to please des Esseintes. The following year, the poet Jean Moreas (1856-1910) published a Manifesto which used the word 'Symbolism' for a new aesthetic,') applying it to poets such as Mallarme, Verlaine and Rimbaud, who went beyond decadence: they evoked a second level of reading, something immaterial more real than the material world, turning their backs on realism.

There were Symbolists and Decadents in the visual arts, too. Some delighted in images of the grotesque and the sinister, like the young Odilon Redon (1840-1916), whose noirs ('blacks') were deeply troubling: most famous of these is the lithograph L' Araignee (Smiling Spider-1885). Like Huysmans, Redon finally moved to Catholicism and finished his work with the extraordinary post-Impressionist murals of Fontfroide Abbey.

The young composer Claude Debussy (1862-1918) sought to do for music what the Symbolists had done for literature. He was inspired by the discovery of Javanese music at the 1889 Exposition. Its rich colours and rhythms and its absence of development revolutionised his thinking. In 1894, his first masterpiece received acclaim: L'Apres-midi d'un faune was

an evocation of Mallarmé's poem in dreamy, apparently formless music, whose 110 bars matched the poem's 110 lines.

This work revolutionized music and brought Debussy fame. Gone were the driving rhythms and dynamic development characteristic of nineteenth-century music. L'Apres-midi does not so much go somewhere as weave a spell or evoke a place of magic and sensuality, a sleepy summer day and the satyr's joys. The specificities and concreteness of realism disappear; the material world exists no longer for itself (if at all) but only to suggest other, deeper truths.

In 1893 Debussy attended the premiere of Pelleas et Melisande, a play by the Belgian Symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck. Set in a nebulous, fairy tale past, the play conveys hopelessness and melancholy. Prince Golaud finds Melisande by a fountain in the wood and marries her, although she cannot say who she is or where she comes from. The story of the play is secondary to its mood and to the constant symbolism of water, from which Melisande emerges and in which she loses her memory, her identity and finally her wedding ring. Golaud, perhaps already fore seeing the end, takes his brother Pelleas to the 'stagnant pool' in the dungeon of the castle: 'Do you smell the odour of death that rises from it?' he asks. 'Your voice!' he exclaims to Melisande. 'It is fresher and purer than water. It is like pure water on my lips.' Pelleas et Melisande carried Symbolism to new heights.

Debussy realised that it was the perfect text for the opera he longed to write. He set the play as it was except for cutting four small scenes. Setting unversified prose to music was revolutionary and brought out the musical qualities of sung French. Finished in 1895, the opera premiered (at the Opera Comique, not the Opera) in 1902. Its floating harmonies and melancholy melodies matched perfectly the eerie ambiguities of the text. It quickly established itself as the most essentially French of all operas and for many the masterpiece of French opera. Both the text and the music reject realism, development and progress. They foreshadow a different time from the developmental and progressive narratives that characterised realism.

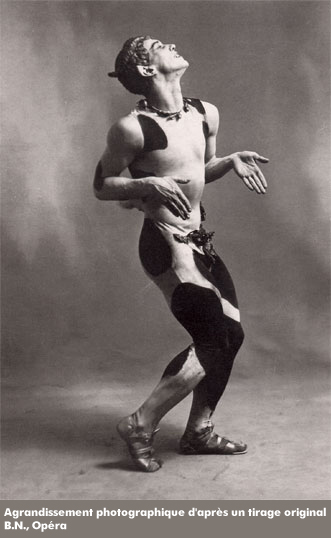

Nijinski Dancing to Debussy's L’Après-midi d’un faune (1912)